Love poetry, the British Woman, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century India

Just when one felt that the final misery had been reached and not another day nor another degree of heat could be borne, with the setting sun the rain came – in a torrential downpour which lasted for forty eight hours. Clad in the briefest, I rush out into the darkness to the still red hot brick chilboutra and let the deluge pour over me, while the thunder rumbled and the lightning played around the inky skies.

Indian Summer

A Mem-sahib in India and Sind

April Swayne – Thomas

Another time we meet

As strangers, friends or who knows

As lovers again

Turn, turn, turn to the rain again.

Strangertime – Pritish Nandy

I have always wondered about the colonial occupation of India during the late eighteen and early nineteenth century, a vast country with breakaway factions of Nawabs and Rajahs who changed their alliances with the changing of summers and the sweltering heat of Indian plains that the British endured during their reign, trying to keep the Union Jack flying. But most of all I was entranced by British women who stayed during those troubled times. British women who fell in love with ordinary Indian men or small time royalty and Indian women who loved and stayed with British Officers during the period of their tenure in India.

Some of them married and stayed back in India. They embraced the culture, could speak fluent Urdu and Hindi and brought a communion so unique which sowed the origins of Indo-English literature or Anglo-Indian creativity.

Kanpur or Cawnpore was one such garrison town. I went to a school which had British teachers, leaving me in awe with their accents and their Indian relatives. The fifties and sixties had a lot of British women who stayed back in India after the independence and partition. The rickshaw that took me to Lalimli Mills and beyond every day was a sojourn I remembered as we encountered British women walking or cycling to various schools in the vicinity.

Gwalior too had its own cluster of Sardars and Nawabs, each with its own palace and even flags. One of my close friends, a former royal still hoist the family colors every morning and lowers it down in the evening. I would have done the same thing as Rajasahab Konera does till today. Among the musty family heirlooms are photographs of beautiful British women married to jagirdars.

1978 was a great year. I became a qualified doctor, still loitering around Park Street in Kolkata, writing poetry and trying to find the ultimate woman who could make me move words closer to the Brahmaputra, Ganga and Thames, in the words of Pritish Nandy, ‘From the other banks…’

1978 was a great year. I became a qualified doctor, still loitering around Park Street in Kolkata, writing poetry and trying to find the ultimate woman who could make me move words closer to the Brahmaputra, Ganga and Thames, in the words of Pritish Nandy, ‘From the other banks…’

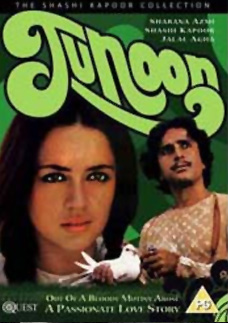

And then came ‘Junoon’.

Everything changed since then.

Ruskin Bond’s novel ‘Flight of the Pigeons’ was adapted by Shyam Benegal and made into a film titled ‘Junoon’. The literal translation from Urdu into English would mean Obsession. But ‘Junoon’ was far more than obsession. The story haunted me, I knew every word was true. It was about a Mughal Nawab who mutinies against the British and falls in love with a British girl.

It is a love story set in Shahjahanpur a small town 250 miles east of Delhi in India, in the period of 1857. That was the time when the British-Indian revolution was in its most definitive phase. Times were changing, loyalties were changing, attitudes were changing, there was hopelessness, fear, despair and most of all obsession and insanity.

It is a love story set in Shahjahanpur a small town 250 miles east of Delhi in India, in the period of 1857. That was the time when the British-Indian revolution was in its most definitive phase. Times were changing, loyalties were changing, attitudes were changing, there was hopelessness, fear, despair and most of all obsession and insanity.

The main theme is about the forbidden love that blossoms amidst all this. Amir Khusru’s poetry rendered in the form of a Qawali during the opening scenes gives a perfect summary of the story.

The events of 1857 were shocking in their violence, and neither the British nor the rebels showed themselves to be very honorable. The word “Junoon” (obsession) connotes a tinge of madness, and that kind of madness is a very appropriate way to view the period. The “love story” is also suffused with the same out-of-control emotion.

Govind Nihlani’s photography brought poetry to a movie which gripped me, I thought often about it.

But poetry is all I thought about.

I wondered about that period which was suffused with such memorable poetry, romanticism that was etched on common conversation in day to day lives. Awadh and Delhi lived on poetry and the British women who came close to the royalty were not untouched. Life was one long summer basked in poems with the beauty of English women who too wrote and spoke poetry, Urdu and English became one, it was only the poem that mattered.

Emma Roberts was one such poet

Emma Roberts was born about 1794 in Methley near Leeds. In the year her mother died and a decision was made to join her sister and her husband Captain Robert Adair McNaughten of the 61st Bengal Infantry to India. Her thoughts on moving to India were stated in one of her books. She stated that ‘There cannot be a more wretched situation than that of a young woman in India who has been induced to follow the fortunes of her married sister under the delusive expectation that she will exchange the privations attached to limited means in England for the far-famed luxuries of the East’ (DNB 1263).

For two years, Roberts was based with her sister around various stations in upper India including Agra, Cawpore and Etawah. Here she wrote of her experiences whilst in India which were published in the Asiatic Journal. These articles accumulated a vast amount of Roberts’ work which was published in her Scenes and Characteristics of Hindoostan (London, 1835). The book was well received in England and, according to Elwood, ‘Her readers trust her, and resign the rein of their imaginations into the author’s hand’ (Dibert-Himes, 1997: 3). The book ‘relates her travels and observations, noting the capacity for making themselves hated; strongly defending Indian servants, especially their honesty, against prejudiced critics’ (Blain et al, 1990: 909).

In 1831, Roberts moved to Calcutta after the death of her sister. Here she devoted herself to her literature and journalism and undertook a job at the local newspaper, The Oriental Observer, as the newspaper editor. Throughout her time in Calcutta she concentrated for the most part on her submissions for the newspaper. In 1832, suffering from overwork, Roberts was forced back to England where she stayed until 1839.

Before leaving India she dedicated a book of poems to her close friend Letitia Elezabeth Landon popularly known all over as L.E.L. called Oriental Scenes, Sketches and Tales (Calcutta 1832) which was rewritten in London in 1832. Whilst in London she wrote articles for the Asiatic Journal and edited the sixty-fourth edition of Mrs. Rundell’s New System of Domestic Cookery (London, 1840. She also completed a biographical sketch of L.E.L., appearing as a memoir in Landon’s collection of poetry called The Zenana and Minor Poems by L.E.L. (1840).

The anguish of her return to England in 1832 due to ill health was captured in the final lines of poetry in Oriental Scenes, Sketches and Tales, which state:

The Ganges! The Ganges! Oh dearer far will be

That narrow winding rivulet, that humble brook to me!

Not all the wealth thy water bears could tempt me to remain,

Or cross the seas to gaze upon thy stately realms again

In September, 1839, Roberts started her second journey to India traveling via an overland route through Europe and Asia. Her record of the journey reveals the arduous nature of the adventure, especially for a lady of that era. By November of that year, Roberts and her traveling companions reached Bombay. Resting at the government house and later settling in the suburb of Parell, she described her experiences in An Overland Journey Through France and Egypt to Bombay (1841, posthumous).

Roberts also became the editor of The Bombay United Service Gazette. At the same time, she became interested in a scheme for providing native Indian women with suitable education and employment. In the same year that she returned to India she published The East India Voyage (1839), a book of travel advice. Soon after she made a visit to Colonel Ovan’s residence at Sattara. In the April of that year she was taken ill and later died on the 16th of September 1840 after being taken to Poonah in order to regain her health. Her last days were spent with her friend Colonel Campbell. Roberts’ adoration of the beauty of India and her enjoyment of her travels was always excited by the anticipation of finally returning to England.

Roberts died leaving the reputation of an extremely talented writer. It was reported by Elwood that Roberts’ death evoked a great response of sorrow in England and a vast amount of tributes were written about her work. Although Emma Roberts work was not fully appreciated at the time, modern day study of the writer and her work reveals her talent and the extent of her skill at recording her observations of India.

One contemporary writer seems to sum up the literature of Roberts perfectly by saying that ‘her business was with the surface of things; her skill consisted in a species of photography, presenting perfect facsimiles of objects, animate and inanimate in their natural forms and hues’ (Dibert-Himes, 1997).

“That Pathan, he’s looking at me.”

– Junoon

Another time we meet

As strangers, friends or who knows

As lovers again

Turn, turn, turn to the rain again.

– Strangertime, Pritish Nandy

There were many poets and writers like Emma Roberts whose literary involvements in the then colonial India were inspired by beauty or sheer love for the people with whom they got attached. Ghazal singers talked about the white skinned beauties and Qawwals sang about them in the court of Mughal Royals.

But most of all whose life and work remains a story in itself, such was Lawrence Hope.

But most of all whose life and work remains a story in itself, such was Lawrence Hope.

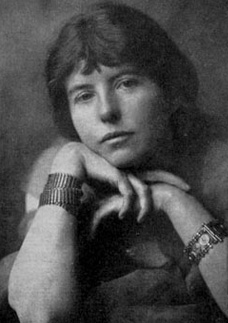

Adela Florence Nicolson (née Cory) (9 April 1865-4 October 1904) was an English poet who wrote under the pseudonym Laurence Hope.

She was born on 9 April 1865 at Stoke Bishop, Gloucestershire, the second of three daughters to Colonel Arthur Cory and Fanny Elizabeth Griffin. Her father was employed in the British army at Lahore, and thus she was raised by her relatives back in England. She left for India in 1881 to join her father. Her father was editor of the Lahore arm of The Civil and Military Gazette, and it was he who in all probability gave Rudyard Kipling (a contemporary of his daughter) his first employment as a journalist. Her sisters Annie Sophie Cory and Isabel Cory also pursued writing careers: Annie wrote popular, racy novels under the pseudonym “Victoria Cross,” while Isabel assisted and then succeeded their father as editor of the Sind Gazette.

Adela married Colonel Malcolm Hassels Nicolson, who was then twice her age and commandant of the 3rd Baluchi Regiment in April 1889. A talented linguist, he introduced her to his love of India and native customs and food, which she began to share. This widely gave the couple a reputation for being eccentric. After he died in a prostate operation, Adela, who had been prone to depression since childhood, committed suicide by poisoning herself and died at the age of 39 on 4 October 1904 in Madras. Her son Malcolm published her Selected Poems posthumously in 1922.

In 1901, she published Garden of Kama, which was published a year later in America under the title India’s Love Lyrics. She attempted to pass these off as translations of various poets, but this claim soon fell under suspicion. Somerset Maugham published a story called The Colonel’s Lady loosely based on the ensuing scandal.

Her poems often used imagery and symbols from the poets of the North-West Frontier of India and the Sufi poets of Persia. She was among the most popular romantic poets of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Her poems are typically about unrequited love and loss and often, the death that followed such an unhappy state of affairs. Many of them have an air of autobiography or confession. Her poetry was extremely popular during the Edwardian period, being hailed by such men as Thomas Hardy, and having two films as well as some musical adaptations of her poetry made, but since then her reputation has faded into near-obscurity. British composer Amy Woodforde-Finden set four of her lyrics from The Garden of Kama to music, the most popular of which was Kashmiri Song; and after these proved a critical success, set four more lyrics from Stars of the Desert (published in 1903) to music as well.

Adela Florence knew Urdu and Hindi and was well conversant with the culture of India during those times. Her poetry is a true reflection of those turbulent times and the passion and obsession of forbidden love.

The Spectator writes in a review in 1901 on the book Indian Love, ‘The poetry of Lawrence Hope must hold a unique place in modern letters. No woman has written lines so full of a strange primeval savagery – a haunting music – the living force of poetry.’

The Daily Chronicle writes in a review in 1901 on the book The Garden of Kama, ‘No one has so truly interpreted the Indian mind – no one, transcribing Indian thought into our literature, has retained so high and serious a level and quite apart from the rarity of themes and setting – the verses remains – true poems.’

Some poems from The Garden of Kama, first published in November 1901. “Less than the dust” is the first poem in this book:

Less than the Dust

Less than the dust, beneath thy Chariot wheel

Less than the rust, that never stained thy Sword

Less than the trust thou hast in me, Oh, Lord,

Even less than these!

Less than the weed, that grows beside thy door,

Less than the speed, of hours, spent far from thee,

Less than the need thou hast in life of me.

Even less am I,

Since I, Oh, Lord, am nothing into thee

See here thy Sword, I make it keen and bright,

Love’s last reward, Death, comes to me tonight,

Farewell, Zahir – u – din.

Kashmiri Song by Juma

You never loved me, and yet to save me,

One unforgettable night you gave me

Such chill embraces as the snow covered heights

Receive from clouds, in northern, Auroral nights.

Such keen communion as the frozen mere

Has with immaculate moonlight, cold and clear,

And all desire,

Like failing fire,

Died slowly, faded surely, and sunk to rest.

Against the delicate chillness of your breast.

This abovementioned poem is her own

The Slave

In purple haze the sun has set,

A tuft of palms, a Minaret,

Rise clear against the sky.

The silence of the scented air

Stirs to a sense of evening prayer

At the muezzin’s cry.

What care have I, that yesterday

I led thee as a slave away

From Maroc’s market-place?

Are we not all the slaves of love?

The very stars that wheel above

Are bound by time and space!

I struck the fetters from thy hands

Only to forge thee stronger bands;

Leastways, ’twas my desire

To hold thy captive soul to me,

Even as mine is chained to thee,

By links of passionate fire.

I want thee for thy beauty’s sake,

Though naught, as owner, will I take;

Thou art entirely free.

Yet, if thy gaze of sombre fire

Find aught in me to wake desire

Then give thyself to me!

Afridi Love

Since, oh, Beloved, you are not even faithful

To me, who loved you so, for one short night,

For one brief space of darkness, though my absence

Did but endure until the dawning light:

Since all your beauty–which was mine–you squandered

On that which now lies dead across your door;

See here this knife, made keen and bright to kill you.

You shall not see the sun rise any more.

Lie still! Lie still! In all the empty village

Who is there left to hear or heed your cry?

All are gone down to labor in the valley,

Who will return before your time to die?

No use to struggle; when I found you sleeping,

I took your hands and bound them to your side,

And both these slender feet, too apt at straying,

Down to the cot on which you lie are tied.

Lie still, Beloved; that dead thing lying yonder,

I hated and I killed, but love is sweet,

And you are more than sweet to me, who love you,

Who decked my eyes with dust from off your feet.

Give me your lips; ah, lovely and disloyal

Give me yourself again; before you go

Down through the darkness of the Great, Blind Portal,

All of life’s best and basest you must know.

Erstwhile, Beloved, you were so young and fragile

I held you gently, as one holds a flower:

But now, God knows, what use to still be tender

To one whose life is done within an hour?

I hurt? What then? Death will not hurt you, dearest,

As you hurt me, just for a single night.

You call me cruel, who laid my life in ruins

To gain one little moment of delight.

Look up, look out, across the open doorway

The sunlight streams. The distant hills are blue.

Look at the pale, pink peach trees in our garden,

Sweet fruit will come of them;–but not for you.

The fair, far snow, upon those jagged mountains

That gnaw against the hard blue Afghan sky

Will soon descend, set free by summer sunshine.

You will not see those torrents sweeping by.

The world is not for you. From this day forward,

You must lie still alone, who would not lie

Alone for one night only, though returning

I was, when earliest dawn should break the sky.

There lies my lute, and many strings are broken,

Some one was playing it, and some one tore

The silken tassels round my Hookah woven;

Some one who plays, and smokes, and loves, no more!

Some one who took last night his fill of pleasure,

As I took mine at dawn! The knife went home

Straight through his heart! God only knows my rapture

Bathing my chill hands in the warm red foam.

And so I pain you? This is only loving,

Wait till I kill you! Ah, this soft curled hair!

Surely the fault was mine, to Love and leave you

Even a single night, you are so fair.

Cold steel is very cooling to the fervor

Of over-passionate ones, Beloved, like you.

Nay, turn your lips to mine. Not quite unlovely

They are as yet, as yet, though quite untrue.

What will your brothers say, to-night returning

With laden camels homewards to the hills,

Finding you dead, and me asleep beside you,

Will he wake me first before he kills?

For I shall sleep. Here on the cot beside you

When you, my Heart’s Delight, are cold in death.

When your young heart and restless lips are silent,

Grown chilly, even beneath my burning breath.

When I have slowly drawn the knife across you,

Taking my pleasure as I see you swoon,

I shall sleep sound, worn out by love’s last fervor,

And then, God grant your kinsmen kill me soon!

The poetry of Laurence Hope remains till today, the finest in the traditions of Indo-English literature. A fitting memorial to her work would be to organize an International Festival on Love Poetry in Chennai where she lies buried. She rightly deserves to be the pioneer in Anglo-Indian literature till today.

“For this is Wisdom; to love, to live To take what fate, or the Gods may give. To ask no question, to make no prayer, To kiss the lips and caress the hair, Speed passion’s ebb as you greet its flow To have, – to hold – and – in time, – let go.”

Laurence Hope

Publications:

• The Garden of Káma, and Other Love Lyrics from India, Arranged in Verse by Laurence Hope. London: William Heinemann, 1901. (English edition)

• India’s Love Lyrics, Including The Garden of Kama. New York: John Lane, 1901.(American edition)

• Stars of the Desert. London: William Heinemann; New York: John Lane, 1903.

• Indian Love. London: William Heinemann, 1905. (English edition)

• Last Poems: Translations from the Book of Indian Love. New York: John Lane; London: William Heinemann, 1905.(American edition)

• Laurence Hope’s Poems. New York: Paul R. Reynolds, 1907.

Illustrated, Selected, and Collected Editions

• Songs from the Garden of Kama. Illustrated with photographs by Mrs. Eardly Wilmot. London: William Heinemann, 1909.

• The Garden of Kama, and Other Love Lyrics from India, Arranged in Verse by Laurence Hope, Illustrated by Byam Shaw. London: William Heinemann; New York: John Lane, 1914.

• Selected Poems from the Indian Love Lyrics of Laurence Hope. Ed. M. J. Nicolson. London: William Heinemann, 1922.

• Complete Love Lyrics: Including India’s Love Lyrics, Stars of the Desert, Last Poems. Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing Co., Inc., 1929.

• Selected Love Lyrics; Containing Poems from India’s Love Lyrics, Stars of the Desert, Last Poems. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1968.

Acknowledgement

• Wikipedia

• Author’s own collection of books by Laurence Hope

• Photography by Kaustav Mitra

January 7, 2007